A brief history of Blue Diamond Garden Centres

1904 was a landmark year for the industry and for the business which was to become the current-day Blue Diamond Group.

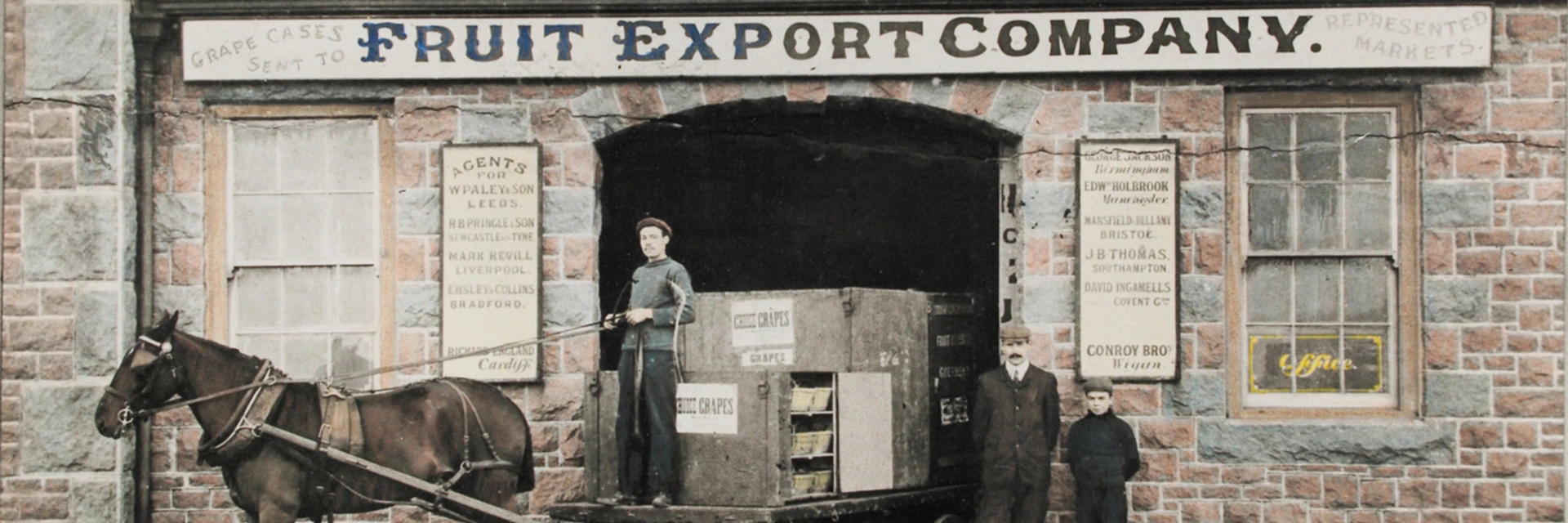

In it's earliest 'guise', Blue Diamond originally emerged as the Fruit Export Company in the beautiful island of Guernsey, Channel Islands. The company was created by a group of prominent local businessmen whose family links still feature today.

John W. Dorey was appointed manager and his son, Percy, was company secretary. the latter proved to be the driving force of the Fruit Export Company.

The company's founders displayed their business skills at an early stage when they acquired a distribution company in the UK with agents scaling the length and breadth of England. This network became the backbone of Fruit Export's success in getting tomatoes to market.

A further stroke of ingenuity saw the company buy wicker baskets locally and go on to commission the manufacture of huge numbers of wooden baskets and then tomato trays.

Today, Blue Diamond is recognised as a genuine Guernsey success story and continues to be owned and managed on the island with plants still at the heart of the business. Blue Diamond now employs around 4,700 employees and 50 garden centres across the UK & Channel Islands.